“The most visible journalism these days — aka the loudest journalism, namely cable news, pop culture blogs, tabloid magazines, TMZ, Buzzfeed, HuffPo, talk radio, etc. — mostly takes the form of opinionated conversation: professional media people discussing current events much like you and your friends might at a crowded lunch table. A side effect of this way of doing journalism is that you rarely hear from anyone who actually is an expert on the subject of interest at any particular time. That approach doesn’t scale; finding and talking to experts is time consuming and experts without axes to grind are boring anyway. So what you get instead are people who are experts at talking about things about which they are inexpert.”

Category Archives: Journalism

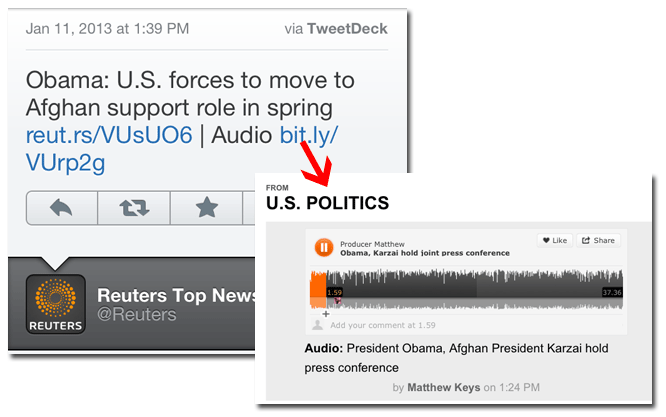

Twitter Radio

Twitter is my first source for breaking news. If anything big (that I care about) happens, it will show up first in my Twitter feed. I guess a cable news channel might come close or a good all-news radio station (do those still exist?) but my Twitter stream is non-stop in my pocket. Smart news organization (NPR and Reuters, for example) know they need to have their stories where I am, rather than try to get me to come to where they are.

Is the future of serious journalism in the hands of corporate media?

ZDNet’s Tom Foremski asks: “As the business models for serious journalism continue to erode where will we get the quality media we need as a society to make important decisions about our future?”

And warns: “Special interest groups will gladly pay for the media they want you to read, but you won’t pay for the media you need to read.”

Cisco has a large team of journalists producing articles about the tech industry for its online magazine “the network.” John Earnhardt said that the reporters have just two rules to follow: “Don’t write about competitors, and don’t write anything that could harm Cisco.”

At Nissan Motors, the company has built a full scale TV studio and produces a news program with veteran journalists from the BBC and elsewhere.

“Why does Nissan want to get into the business of serious news journalism? Why not sponsor an existing news show? His answer was surprising. “I don’t have the confidence that traditional news organizations will be able to survive the transition to the new business models. Why should I invest large amounts of money over the next few years in a failing enterprise?”

If there’s a take-away from this piece it’s probably this: “Media is a loss leader, you need something else to sell. If all you have is media to sell, then you will have losses.”

What does mobile explosion mean for news?

Some nuggets from new Pew Research Center report based on a survey of 9,513 U.S. adults conducted from June-August 2012 (including 4,638 mobile device owners)

- Half of all U.S. adults now have a mobile connection to the web through either a smartphone or tablet

- Nearly a quarter of U.S. adults, 22%, now own a tablet device-double the number from a year earlier

- 64% of tablet owners and 62% of smartphone owners say they use the devices for news at least weekly

- As many as 43% say the news they get on their tablets is adding to their overall news consumption. And almost a third, 31%, said they get news from new sources on their tablet

- Fully 60% of tablet news users mainly use the browser to get news on their tablet, just 23% get news mostly through apps and 16% use both equally

The Business of War (VICE News)

In the last couple of days I’ve watched three or four news documentaries produced by Vice. The one below is titled “The Business of War: SOFEX”

If you invest the 20 minutes to watch this you might conclude — as I did — the world is fucked. Not a little bit fucked. Not “It’s okay, I think we can un-fuck this.” We are Ving-Rhames-Pulp-Fiction fucked.

This documentary explains SO much of what is happening in the world. As you watch it, try to imagine Anderson Cooper or Brian Williams (and the corporations they work for) doing this kind of reporting.

As I watched these reports, I kept contrasting them to the network news formats of the past 20+ years. Half-hour summaries with forest fires and floods at the top, followed by fluffy pretend news at the bottom. With lots and lots of commercials mixed in.

In all fairness, you can sort of imagine a piece like the one below on 60 Minutes but only after the teeth have been extracted.

I spotted the link to this documentary in my Twitter stream. I can play these on my iPhone, any time, anywhere. Or, using AirPlay to stream them to my big screen, watch them at home via Apple TV.

I can only assume the gasping, lumbering news organzations of yore know they are irrelevant but just don’t know what to do about it.

There is nothing on CNN or Fox or XYZ for which I’d pay cash money. But yeah, I’d pay for reporting this good.

The MP3 of journalism

“But we are in the midst of a transformative shift in the craft of journalism. Text-only stories, the kind your parents found in their morning newspapers and characterized by the classic inverted pyramid (most important stuff at the top, least important stuff at the bottom) could eventually go the way of 45-rpm records. The MP3 of journalism may be the “live blog,” which relies on the merging of platforms and weaving of text with video, audio, external links to other articles (including those of rival news organizations), blogs, tweets, Facebook posts, and whatever other useful information is available. It doesn’t matter if information originates from a New York Times article, a tweet from an eyewitness on the scene, or someone offering astute commentary and curating links, a video shot by a protester or produced by a team at CNN. Because in the live blog format disparate platforms become irrelevant, and the walls between these separate silos of content simply dissolve.”

When experts don’t seem so “expert”

This is an excerpt from a post by Terry Heaton, one of the handful of thinkers I look to first for an understanding of what’s happening in the world. The link to his post is below, but the following paragraphs can stand on their own.

Our culture is based upon hierarchical layers of “expertise,” some of it licensed by the state. This produces order, which Henry Adams called “the dream of man.”

It also produces elites, the governing class, those who call the shots for others not so fortunate as to occupy the higher altitudes. This is the 1% against which the occupiers bring their protests, their dis-order.

We used to think that elites and hierarchical order were necessary for the well-being of all, but that idea is being challenged as knowledge — the protected source of power (and elevation) — is being spread sideways along the Great Horizontal. It’s not that we’re so much smarter than we used to be; it’s that the experts don’t seem so “expert” anymore, because the knowledge that gave them their status isn’t protected today. Anybody can access it with the touch of a finger.

This is giving institutions fits, and each one is fighting for its very life against the inevitable flattening that’s taking place. Medicine wants no part of smart and informed patients and neither does the insurance industry. The legal world scoffs at the notion that they’re in it for themselves as they occupy legislatures and create the laws that work on their behalf. Higher education increasingly touts the campus experience over what’s being learned, because they all know that the Web has unlimited teaching capacity. Government needs its silos to sustain its bureaucracy, but the Great Horizontal cuts across them all.

I added the emphasis in graf 3. For me, this is The Big Idea of the early 21st century. The high-speed smart phone in my pocket means you don’t necessarily know more than I do, so why the fuck should you be in charge?

What an exciting time to be alive. And sure to get exciting-er.

We need more chaos in the news business

Clay Shirky argues we need for the news business to be more chaotic than it is because ” there are many more ways of getting and reporting the news that we haven’t tried than that we have.” Here are some excerpts from his latest essay:

Buy a newspaper. Cut it up. Throw away the ads. Sort the remaining stories into piles. Now, describe the editorial logic holding those piles together.

—

For all that selling such a bundle was a business, though, people have never actually paid for news. We have, at most, helped pay for the things that paid for the news.

—

But even in their worst days, newspapers supported the minority of journalists reporting actual news, for the minority of citizens who cared.

—

I could tell (my) students that when I was growing up, the only news I read was thrown into our front yard by a boy on a bicycle. They might find this interesting, but only in the way I found it interesting that my father had grown up without indoor plumbing.

—

News has to be subsidized because society’s truth-tellers can’t be supported by what their work would fetch on the open market. Real news—reporting done for citizens instead of consumers—is a public good.

—

A 30% reduction in newsroom staff, with more to come, means this is the crisis, right now. Any way of creating news that gets cost below income, however odd, is a good way, and any way that doesn’t, however hallowed, is bad.

“Bottom-Up Revolution”

From an opinion piece on Al-Jazeera, by Paul Rosenberg

Obama, however, is just one political figure, reflecting the more general state of US politics – particularly elite opinion and major economic interests. His ambivalence is, in this sense, an expression of America’s fading power. Obama’s belated attempts to play catch-up with the Arab Spring are but one facet of a more general loss of previous dominance.

And this from Wadah Khanfar, on the obsolecense aging Arab regimes:

This outstanding change, this historic moment, was totally lost on ageing governments that thought they were dealing with a bunch of kids who only needed to vent and then go home to their aimless lives. But they were wrong: because their ideas were old, their opinions were old, their minds were old, and their spirit was old. Ignorance can sometimes be a tool of destiny.

I’m finding Al-Jazeera a very credible and refreshing source for world news.

And then there’s this from a recent NYT story:

The Obama administration is leading a global effort to deploy “shadow” Internet and mobile phone systems that dissidents can use to undermine repressive governments that seek to silence them by censoring or shutting down telecommunications networks.

The effort includes secretive projects to create independent cellphone networks inside foreign countries, as well as one operation out of a spy novel in a fifth-floor shop on L Street in Washington, where a group of young entrepreneurs who look as if they could be in a garage band are fitting deceptively innocent-looking hardware into a prototype “Internet in a suitcase.”

Reminds me of all those Stinger missles we gave the Taliban fighters to use against the Russkies.

Everywhere media

Like many others, I followed news of the destruction of Joplin, Missouri, on Twitter. A tornado destroyed most of the southeast Missouri town and almost immediately videos and photos began showing up on YouTube, Facebook and Twitter.

It brought back memories of my radio days.

Our station had an old Army surplus radar that gave us something of a competitive edge when it came to storm coverage. We also relied on news from the National Weather Service that came in on a teletype. And the local weather spotters who radio’d eyeball reports in.

Then one night a big storm hit and I scurried out to the station only to discover power from the city was out. But we were able to broadcast thanks to a generator that just ran our transmitter and one studio. No radar, no teletype, zip.

So I started taking phone calls from listeners who described what was happening where they were. We did that for most of an hour.

Most old radio guys have lots of stories like that. Bad weather was radio’s time to shine.

When I started working for a statewide radio network in 1984, it was frustrating not to be able to talk directly to the listeners, especially when a big story –like a tornado– was breaking. We only got on the air if our affiliates chose to put us on the air.

Same deal for covering the story. If the story was hundreds of miles away, we had to rely on our affiliate stations to send us reports we then put on the statewide network. And many of them did/do a remarkable job.

Assuming the radio stations in Joplin are on the air, our newsroom was probably getting reports last night.

This is what I was thinking about last night as I watched my twitter feed fill up with links to video and photos and first-hand accounts of the “devastation” (a term that has now been used so many times as to be almost meaningless).

At least two of our reporters –one in Missouri and one in Wisconsin– were re-tweeting reports about the big storms in their respective states. I was glad to see that and not very worried about the accuracy. The sources they were re-tweeting were credible.

It reminded me of a story about the BBC which has “a special desk that sits in the middle of the newsroom and pulls in reports from Twitter, Facebook, Flickr, YouTube and anywhere else it can find information.”

Whatever the disaster… natural or man-made… someone is there with a video camera and within minutes the story is being “reported.” What this means for ‘traditional’ news organizations like ours is still being worked out but it’s clear it will never be like it was.