The war in Afghanistan seems very… abstract to me. I know it’s going on and people are dying (although we see almost no images of that) but it doesn’t seem real. Junger’s book (and the documentary, I assume) makes it seem very real.

I can’t tell if Junger has any views about whether the war is right or wrong or if that’s even a relevant question from the perspective the people fighting it. But his account makes it difficult to imagine anything like “winning.”

“The moral basis of the war doesn’t seem to interest soldiers much, and its long-term success or failure has a relevance of almost zero. Soldiers worry about those things about as much as farmhands worry about the global economy, which is to say, they recognize stupidity when it’s right in front of them but they generally leave the big picture to others.” – page 25

“…at one mile out (an) aircraft carrier is the size of a pencil eraser held at arm’s length. The plane covers that distance in thirty-six seconds and must land on a section of flight deck measuring seven yards wide and forty-five yards long.” – page 34

“…he joined the Army because he was tired of partying and living at this mother’s house, and now he’s behind sandbags on a hilltop in Afghanistan getting absolutely rocked.” – page 67

“Once while leaning against some sandbags I was surprised to feel some dirt fly in my face. It didn’t make any sense until I heard the gunshots a second later. How close was that round? Six inches? A foot?” – page 71

“It certainly isn’t beautiful up there, but the fact that it might be the last place you’ll ever see does give it a kind of glow.” – page 71

“The problem with fear, though, is that it isn’t any one thing. Fear has a whole taxonomy — anxiety, dread, panic, foreboding — and you could be braced for one form and completely fall apart facing another.” – page 73

“If I had any illusions about personal courage, they dissolved in the days or hours before something big, dread accumulating in my blood like some kind of toxin until I felt too apathetic to even tie my boots properly.” – page 74

“There are different kinds of strength, and containing fear may be the most profound, the one without which armies couldn’t function and wars couldn’t be fought (God forbid).” – page 74

“…an enormous amount of war-fighting simply consists of carrying heavy loads uphill.” – page 75

“If you’re not prepared to walk for someone you’re certainly not prepared to die for them, and that goes to the heart of whether you should even be in the platoon.” – page 77

“(He) had some kind of crazy redneck strength that was more like hydraulics than musculature.” – page 75

“The fact that networks of highly mobile amateurs can confound –even defeat– a professional army is the only thing that has prevented empires from completely determining the course of history. You can’t predict the outcome of a war simply by looking at the numbers.” – page 83

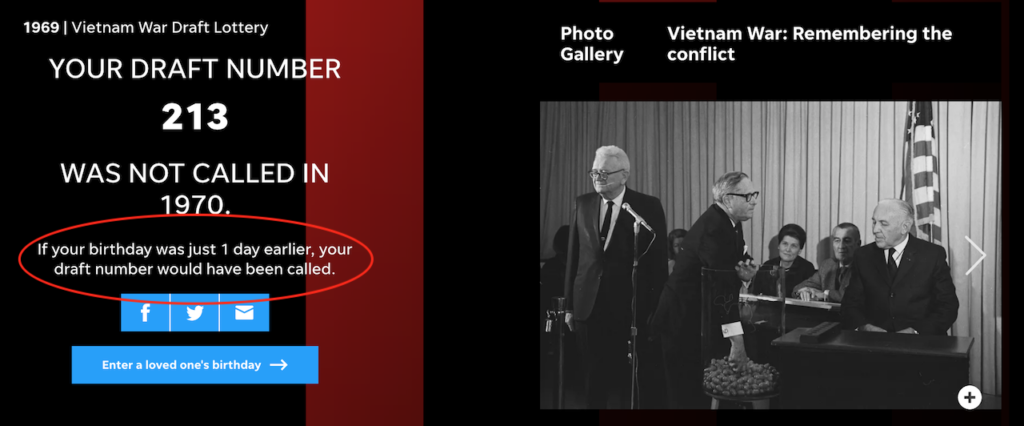

A “Vietnam moment” was one in which you weren’t so much getting misled as getting asked to participate in a kind of collective wishful thinking.” – page 132

“…much of modern military tactics is geared toward maneuvering the enemy into a position where they can essentially be massacred from safety. It sounds dishonorable only if you imagine that modern war is about honor; it’s not. It’s about winning, which means killing the enemy on the most unequal terms possible. Anything less simply results in the loss of more of your own men.” – page 140

“The enemy now had a weapon that unnerved the Americans more than small-arms fire ever could: random luck. Every time you drove down the road you were engaged in a twisted existential exercise where each moment was the only proof you’d ever have that you hadn’t been blown up the moment before.” – page 142

“War is a lot of things and it’s useless to pretend exciting isn’t one of them. It’s insanely exciting. The machinery of war and the sound it makes and the urgency of its use and the consequences of almost everything about it are the most exciting things anyone engaged in war will ever know.”

“War is supposed to feel bad because undeniably bad things happen in it, but for a nineteen-year-old at the working end of a .50 cal during a firefight that everyone comes out of okay, war is life multiplied by some number that no one has ever heard of.” – page 144

“The moral basis of the war doesn’t seem to interest soldiers much, and its long-term success or failure has a relevance of almost zero. Soldiers worry about those things about as much as farmhands worry about the global economy, which is to say, they recognize stupidity when it’s right in front of them but they generally leave the big picture to others.” – page 25

“…at one mile out (an) aircraft carrier is the size of a pencil eraser held at arm’s length. The plane covers that distance in thirty-six seconds and must land on a section of flight deck measuring seven yards wide and forty-five yards long.” – page 34

“…he joined the Army because he was tired of partying and living at this mother’s house, and now he’s behind sandbags on a hilltop in Afghanistan getting absolutely rocked.” – page 67

“Once while leaning against some sandbags I was surprised to feel some dirt fly in my face. It didn’t make any sense until I heard the gunshots a second later. How close was that round? Six inches? A foot?” – page 71

“It certainly isn’t beautiful up there, but the fact that it might be the last place you’ll ever see does give it a kind of glow.” – page 71

“The problem with fear, though, is that it isn’t any one thing. Fear has a whole taxonomy — anxiety, dread, panic, foreboding — and you could be braced for one form and completely fall apart facing another.” – page 73

“If I had any illusions about personal courage, they dissolved in the days or hours before something big, dread accumulating in my blood like some kind of toxin until I felt too apathetic to even tie my boots properly.” – page 74

“There are different kinds of strength, and containing fear may be the most profound, the one without which armies couldn’t function and wars couldn’t be fought (God forbid).” – page 74

“…an enormous amount of war-fighting simply consists of carrying heavy loads uphill.” – page 75

“If you’re not prepared to walk for someone you’re certainly not prepared to die for them, and that goes to the heart of whether you should even be in the platoon.” – page 77

“(He) had some kind of crazy redneck strength that was more like hydraulics than musculature.” – page 75

“The fact that networks of highly mobile amateurs can confound –even defeat– a professional army is the only thing that has prevented empires from completely determining the course of history. You can’t predict the outcome of a war simply by looking at the numbers.” – page 83

A “Vietnam moment” was one in which you weren’t so much getting misled as getting asked to participate in a kind of collective wishful thinking.” – page 132

“…much of modern military tactics is geared toward maneuvering the enemy into a position where they can essentially be massacred from safety. It sounds dishonorable only if you imagine that modern war is about honor; it’s not. It’s about winning, which means killing the enemy on the most unequal terms possible. Anything less simply results in the loss of more of your own men.” – page 140

“The enemy now had a weapon that unnerved the Americans more than small-arms fire ever could: random luck. Every time you drove down the road you were engaged in a twisted existential exercise where each moment was the only proof you’d ever have that you hadn’t been blown up the moment before.” – page 142

“War is a lot of things and it’s useless to pretend exciting isn’t one of them. It’s insanely exciting. The machinery of war and the sound it makes and the urgency of its use and the consequences of almost everything about it are the most exciting things anyone engaged in war will ever know.”

“War is supposed to feel bad because undeniably bad things happen in it, but for a nineteen-year-old at the working end of a .50 cal during a firefight that everyone comes out of okay, war is life multiplied by some number that no one has ever heard of.” – page 144

I was talking with a co-worker about Lara Logan’s (CBS Chief Foreign Correspondent) recent appearance on The Daily Show. She posed the question, “When was the last time you saw a dead American soldier on TV?” She was making the point that media in the U. S. has been MIA on the war in Iraq (except for that victorious march into Baghdad).

I was talking with a co-worker about Lara Logan’s (CBS Chief Foreign Correspondent) recent appearance on The Daily Show. She posed the question, “When was the last time you saw a dead American soldier on TV?” She was making the point that media in the U. S. has been MIA on the war in Iraq (except for that victorious march into Baghdad).