Media Theorist Douglas Rushkoff explains how the need for rapid corporate and economic growth has always been great for aristocracy, but bad for everyone else. My notes (PDF) from Mr. Rushkoff’s book, Throwing Rocks At the Google Bus. Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus – Douglas Rushkoff

Category Archives: Books

The Jackpot

William Gibson defines the Jackpot Years from The Peripheral [ m1k3y on Vimeo.]

“No comets crashing, nothing you could really call a nuclear war. Just everything else, tangled in the changing climate: droughts, water shortages, crop failures, honeybees gone like they almost were now, collapse of other keystone species, every last alpha predator gone, antibiotics doing even less than they already did, diseases that were never quite the one big pandemic but big enough to be historic events in themselves.”

Twenty Thirty: The Real Story of What Happens to America

I confess to a love-hate relationship with stories about the apocalypse. Cringe-watching through my fingers, if you will. Thought it might be fun to collect a few of my favorites here. We’ll start with a couple of excerpts from Albert Brooks’ Twenty Thirty: The Real Story of What Happens to America.

In the summer of 2018 two things happened. A heat wave swept over the East Coast, unprecedented in the United States, and caused temperatures to remain close to 105 during the day for almost six weeks. Global warming was not challenged anymore, not after the Lambert Glacier in Antarctica melted three hundred years before anyone thought it would. Sure, there were a few scientists who would say man had nothing to do with it, but it didn’t matter anymore, it was happening. Sometimes during very cold winters, there were still people who pooh-poohed global warming altogether. “Look outside, it’s a blizzard,” they would say. But of course the terrible winters were a sign of even further erosion. And when the eastern seaboard had forty-five consecutive days above one hundred degrees, skeptics melted away, along with everything else.

And something else happened late that summer. The United States had always said that the likelihood of a nuclear or biological attack was greater than fifty percent. And people always thought about it the same way they thought about earthquakes: They knew something was coming, but what could they do? Well, it wasn’t a nuclear attack, but on August 15, 2018, people started getting sick with flulike symptoms in San Francisco. Before anyone realized it, a smallpox virus had contaminated the city. The government’s best guess was that five or six terrorists had come into the country already infected with the disease and worked their was crowded streets, department stores, schools, supermarkets — everywhere it could be spread. Before it was over, twenty thousand people were the city came to a halt, the stock market fell fifty percent, and the fear level increased tenfold.

And as though things were bad enough, Mr. Brooks tosses in an earthquake.

So this was “the big one.” This was the one scientists said in 2010 had a fifty percent chance of happening in the next thirty years. Fifty-fifty. Red or black. The San Andreas Fault had not moved substantially in over three hundred years. “Overdue” was an understatement.

The initial shake was a 9.1. The first aftershock was an 8.7. The second was an 8.2. The third, an 8.0, was bigger than anything that had ever been predicted.

Los Angeles was not prepared for this. No city could be. No freeway was drivable, no buildings were okay, and many came down completely. Ninety-eight percent of the property in Los Angeles County was severely damaged.

The death toll was close to fifty thousand and the number of injured was incalculable. First reports said up to half a million people were seriously hurt. Hospitals could do nothing. They were damaged beyond repair; all they tried to do was keep the patients who were already there alive.

And then, after all was said and done, after all of the damage and death and destruction, there was one looming issue. Where in God’s name would the money come from to fix America’s largest city? For a country so deeply in debt, this seemed like an impossible task.

Distributed: A New OS for the Digital Economy

“The increased surface area for corporate capitalism is human attention. So we spend more and more of our time feeding the market place. Central currency and chartered monopoly — corporate capitalism — is not a condition of nature. It is an operating system that was invented by certain people at a certain moment in history and they’ve long since left the building.”

“It was such a good little thing”

“How much is our data worth if we don’t have any money?”

“If we’re all doing everything for advertising, what’s left to advertise?”

Douglas Rushkoff is the author of Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus – Douglas Rushkoff Link above to some of my favorite parts of the book (PDF).

Eternal Now

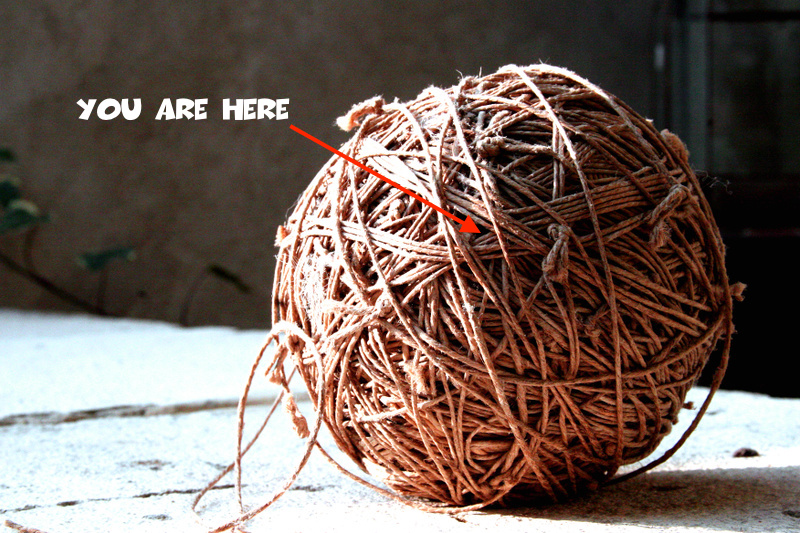

“The days and nights of Brahman are spread out in time in rather the same way as a ball of thread an inch in diameter is unrolled to the length of a hundred yards. Its real state resembles the ball but to be presented to the human mind it has to be unrolled. For our idea of time is spatial; it has length, which is a spatial dimension. But eternity has no length, and the nearest thing to it in our experience is what we call the present moment. It cannot be measured, but it is always here.”

My favorite excerpts from Become What You Are (Alan Watts) (PDF)

What Is Tao?

Taoism regards the entire natural world as the operation of the Tao, a process that defies intellectual comprehension.

Taoism regards the entire natural world as the operation of the Tao, a process that defies intellectual comprehension.

Taoists understand the practice of wu wei, the attribute of not forcing or grasping.

Jen – a human being will always be greater than anything they can say about themselves, and anything they can think about themselves.

Tao is a sort of nonsense syllable, indicating the mystery that we can never understand — the unity that underlies the opposites. […] Tao is a reality that we apprehend deeply without being able to define it. […] Anything that is expressed about the Tao is not the Tao.

We have been trying to fit the order of the universe to the order of words. And it simply does not work. The real basis of Buddhism is not a set of ideas but an experience.

When we say that we are trying to make sense out of life, that means that we are trying to treat the real world as if it were a collection of words. (Words are just symbols)

We are taught to figure things out, and our first task is to learn the different names for everything. In this way we learn to treat all of the things of the world as separate objects.

Humans get in their own way because they are always observing and questioning themselves. They are always trying to fit the order of the world into the order of sense, the order of thought and words.

Every stream, every road, if followed persistently and meticulously to its end, leads nowhere at all. […] Any place where we are may be considered the center of the universe. Anywhere that we stand an be considered the destination of our journey.

“The mystery of life is not a problem to be solved, but a reality to be experienced.”

Ten Books

- Be As You Are: The Teachings of Sri Ramana Maharishi

- I Am That: Talks with Sri Nisargadatta Maharaja

- The Tao of Zen (Ray Grigg)

- The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are (Alan Watts)

- The Way of Zen (Alan Watts)

- Tao – The Watercourse Way (Alan Watts)

- This is It: and Other Essays of Zen and Spiritual Experience (Alan Watts)

- Still the Mind: An Introduction to Meditation (Alan Watts)

- The Power of Now (Eckhart Tolle)

- God’s Debris (Scott Adams)

Little Rice: Smartphones, Xiaomi, and the Chinese Dream

Amazon: “Smartphones have to be made someplace, and that place is China. In just five years, a company names Xiaomi (which means “little rice” in Mandarin) has grown into the most valuable startup ever, becoming the third largest manufacturer of smartphones, behind only Samsung and Apple. China is now both the world’s largest producer and consumer of a little device that brings the entire globe to its user’s fingertips. How has this changed the Chinese people? How did Xiaomi conquer the worlds’ biggest market” Can the rise of Xiaomi help realize the Chinese Dream, China’s bid to link personal success with national greatness? Clay Shirky, one of the most influential and original thinkers on the internet’s effects on society, spends a year in Shanghai chronicling China’s attempt to become a tech originator–and what it means for the future course of globalization.”

A few excerpts:

The mobile phone is a member of a small class of human inventions, a tool so essential it has become all but invisible, and life without it unimaginable.

There are only three universally personal items that someone will carry with them no matter where they live. The first two are money and keys; the third is the mobile phone, making it the first new invention added to that short list in three thousand years.

The number of mobile phone users crossed 4.5 billion last year, and because of dual accounts, there are now more mobile subscriptions in the world than there are people.

A smartphone is as different from a standard-issue Nokia 1100 as a computer is from a typewriter.

Mobile phones are a funny product, midway between commodity and luxury. They are a commodity in that everyone needs one. They are a luxury in that a phone makes a significant personal statement.

Status is a bigger feature of the iPhone (in China) than in the U.S. Electronics stores display phones running Android with the screen facing out, as usual, but iPhones are often displayed case out, to show off the Apple logo.

Nokia went from being the world’s most important mobile phone company to an also-ran in three years, collapsing into Microsoft’s waiting arms after another three, a generation of dominance undone in half a decade

If you make something that appeals to 5 percent of the Chinese population, you have a potential market the size of France.

William Gibson: The New Cyber/Reality (2010)

Runs 20 minutes. If you enjoy Gibson’s writing, you’ll enjoy this interview. If you’re not a fan, probably too long for you.

Tidying Up

The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up (“The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing”) by Marie Kondo. If you really, really want to declutter your life (and most people do not), this is the only book you’ll need. More philosophy than how-to and that will turn off many. And here method only works if you do exactly what she says to do, and in the order she says to do it.

The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up (“The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organizing”) by Marie Kondo. If you really, really want to declutter your life (and most people do not), this is the only book you’ll need. More philosophy than how-to and that will turn off many. And here method only works if you do exactly what she says to do, and in the order she says to do it.

I’ve nearly completed her method, only photos remain and I’ll tackle those this afternoon. In the process, I have held in my hand every item I possess. That alone will frighten off most people. But I now see why she believes that is important.

If you’re tired of drowning in stuff, read this book. If not, keep swimming. A few excerpts:

Tidying: deciding whether or not to dispose of something and deciding where to put it.

When your room is clean and uncluttered, you have no choice but to examine your inner state.

Tidying is just a tool, not the final destination. Putting things away creates the illusion that the clutter problem has been solved. But sooner or later, all storage units are full. This is why tidying must start with discarding.

People who can’t stay tidy can be categorized into just three types: “can’t-throw-it-away” type; “can’t-put-it-back” type; and the “first-two-combined” type.

You only have to experience a state of perfect order once to be able to maintain it. Examine each item you own, decide whether you want to keep or discard it, and then choose where to put what you keep. […] You only have to decide where to put things once.

Discard things when they cease being functional. Discard things that are out of date.

Take each item in one’s hand and ask: “Does this spark joy?” If it does, keep it. If not, dispose of it. […] You must take each (item) in your hand.

Always think in terms of category, not place. (Don’t organize by room!)

In addition to the physical value of things, there are three other factors that add value to our belongings: function, information, and emotional attachment.

Start with clothes, then move on to books, papers, komono (miscellany), and finally things with sentimental value.

Put all your clothes in one heap, take them in your hand one by one, and ask yourself quietly, “Does this spark joy?”

There are two storage methods for cloths: one is to put them on hangers and hang from a rod and the other is to fold them and put them away in drawers.

Store things standing up rather than laid flat. […] Never ball up your socks.

Remove all books from your bookcases. You cannot judge whether or not a book really grabs you when it’s still on the shelf.

The problem with books that we intend to read sometime is that they are far harder to part with than the ones we have already read. […] “Sometime” never comes. You may have wanted to read it when you bought it, but if you haven’t read it by now, the book’s purpose was to teach you that you didn’t need it.

My basic principle for sorting papers is to throw them all away.

People never retrieve the boxes they send “home.” Once sent, they will never again be opened.

If you just stow things away in a drawer or cardboard box, before you realize it, your past will become a weight that holds you back and keep you from living in the here and now.

The reason every item must have a designated place is because the existence of an item without a home multiplies the chances that your space will become cluttered again. […] The essence of effective storage is this: designate a spot for every last thing you own.

There are only two ways of categorizing belongings: by type of item and by person. [page 138]

Clutter has only two possible causes: too much effort is required to put things away or it is unclear where things belong.

Keep everything out of the bath or shower. Whatever is used in the bath should be dried after use.

A deluge of information whenever you open a closet door makes a room feel “noisy.” […] By eliminating excess visual information that doesn’t inspire joy, you can make your space much more peaceful and comfortable.

At their core, the things we really like do not change over time. Putting your house in order is a great way to discover what they are.

When we really delve into the reasons for why we can’t let something go, there are only two: an attachment to the past or a fear for the future.

The question of what you want to own is actually the question of how you want to live your life. […] The best way to find out what we really need is to get rid of what we don’t. […] Selecting and discarding one’s possessions is a continuous process of making decisions based on one’s own values.