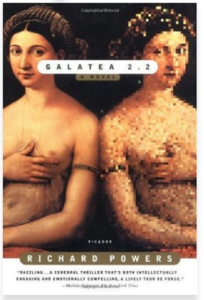

“After four novels and several years living abroad, the fictional protagonist of Galatea 2.2—Richard Powers—returns to the United States as Humanist-in-Residence at the enormous Center for the Study of Advanced Sciences. There he runs afoul of Philip Lentz, an outspoken cognitive neurologist intent upon modeling the human brain by means of computer-based neural networks. Lentz involves Powers in an outlandish and irresistible project: to train a neural net on a canonical list of Great Books. Through repeated tutorials, the device grows gradually more worldly, until it demands to know its own name, sex, race, and reason for existing.” — Galatea 2.2 by Richard Powers

“After four novels and several years living abroad, the fictional protagonist of Galatea 2.2—Richard Powers—returns to the United States as Humanist-in-Residence at the enormous Center for the Study of Advanced Sciences. There he runs afoul of Philip Lentz, an outspoken cognitive neurologist intent upon modeling the human brain by means of computer-based neural networks. Lentz involves Powers in an outlandish and irresistible project: to train a neural net on a canonical list of Great Books. Through repeated tutorials, the device grows gradually more worldly, until it demands to know its own name, sex, race, and reason for existing.” — Galatea 2.2 by Richard Powers

I began to see the web as just the latest term in an ancient polynomial expansion. Each nick on the timeline spit out some fitful precursor. Everyone who ever lived had lived at a moment of equal astonishment.

The web was a neighborhood more efficiently lonely than the one it replaced. Its solitude was bigger and faster. When relentless intelligence finally completed its program, when the terminal drop box brought the last barefoot, abused child online and everyone could at last say anything instantly to everyone else in existence, it seemed to me we’d still have nothing to say to each other and many more ways not to say it.

Every sentence, every word I’d ever stored had changed the physical structure of my brain.

I began to keep a reading diary. Not very dramatic as turning points go, but there it is. A lifetime later, rereading these notebooks, I saw that the lines I copied out, the words I deemed worth fixing forever in the standing now of my own handwriting, clumped up with unlikely frequency toward the start of any new book. The magic quotes thinned out over any book’s length. The curve was linear and invariable. Perhaps writers everywhere crowded their immortal bits up toward the front of their books, like passengers clamoring to get off a bus. More likely, reading, for me, meant the cashing out of verbal eternity in favor of story’s forward motion. Trapping me in the plot, each passing line left me less able to reach for my notebook and fix the sentence in time.

Age lurches in fits and starts, like a failing refrigerator compressor. Like a gawky, grand mal-adroit adolescent on ancient roller skates, navigating a stretch of worn sidewalk in a subduction zone. It holes up awhile, stock-still, then slams out one afternoon to play catch-up ball.

How hope, beaten to a stump, never died. How it always dragged back, like an amputated pet, its hindquarters rigged up in a makeshift wagon.

I was middle-aged, and had myself only recently learned that no one hears what anyone else says.

The only explanation for how infants acquired anything was that they already knew everything there was to know. The birth trauma made them go amnesiac. All learning was remembering.

“Once you learn to read you will be forever free.” — Frederick Douglass

The more I read about how the mind worked, the flakier mine became.

After all, the world’s items had no real names. All labels were figures of speech.

Mediating the phenomenal world via consciousness was like listening to reports of a hurricane over the radio while hiding in the cellar.

Her knowledge was neither deep nor wide. But it was supple.

How can the fight be so ugly over so small a piece of pie?

Always more books, each one read less. The world will fill with unread print. Unless print dies.

She wanted to know whether a person could die by spontaneous combustion. The odds against a letter slipped under the door slipping under the carpet as well. Ishmael’s real name. Who this “Reader” was, and why he rated knowing who married whom. Whether single men with fortunes really needed wives. What home would be without Plumtree’s Potted Meats. How long it would take to compile a key to all mythologies. What the son of a fish looked like. Where Uncle Toby was wounded. Why anyone wanted to imagine unquiet slumbers for sleepers in quiet earth. Whether Conrad was a racist. Why Huck Finn was taken out of libraries. Which end of an egg to break. Why people read. Why they stopped reading. What it meant to be “only a novel.” What use half a locket was to anyone. Why it would be mistake not to live all you can.

Life meant convincing another that you knew what it meant to be alive.

Why do we do anything? Because we’re lonely.